Tokko "Kamikaze" Special Attack Doctrine

Contributor: C. Peter Chen

In Sep 1944, the Japanese Army 4th Air Army and the Japanese Navy 1st Air Fleet conducted tests and concluded that tokko, short for tokubetsu kogeki or "special attack", during which the pilot carried the bomb all the way through the dive and releasing only a split second before the aircraft struck the enemy ship, was much more effective than the standard anti-ship bombing technique during which only one in four skills crews could score hits with bombs. The first authorized tokko attack took place on 13 Sep 1944 by Army planes based at Los Negros, Philippine Islands. On 17 Oct 1944, Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi took command of the 1st Air Fleet, and soon organized a special unit within the 201st Air Group based in the Philippine Islands named Shimpu Tokubetsu Kogeki Tai, or "Divine Wind Special Attack Unit". The kanji characters used for shimpu could also be read as kamikaze especially in modern usage; despite Onishi's usage of shimpu as the pronunciation, kamikaze became the common pronunciation in western literature.

A tokko usually began with dispatch from a communications center, whose information came from forward reconnaissance aircraft. The special attack air group commander would then determine the attack force's size base on weather, enemy strength, and the overall tactical objective. While the air group commander briefed the pilots, the ground crew fueled, armed, and warmed up the aircraft. The standard special attack aircraft were usually fighters or other similar light aircraft, while the standard armament were either four 60 kilogram or one 250 kilogram bombs.

Depending on distance to the enemy and weather conditions, commanders determined the best launch time in order to reach the enemy at 1820 at the latest. The time was chosen in order to avoid reaching the enemy after sunset, after which time finding enemy vessels and selecting targets would become difficult. Some air group commanders preferred dawn attacks if the option was available to them. Dawn time attacks tend to encounter the least number of enemy interceptors en route.

A standard special attack group consisted of three tokko aircraft and two escort aircraft. The reason for such a formation was because the formation must be kept small enough to be launched in a short amount of time and could maneuver with maximum mobility. Three kamikaze aircraft was determined to be optimal as sometimes against a larger target such as a fleet carrier, multiple hits might be necessary to sink or disable the target.

The two escorts were very important for that they were charged with warding off enemy interceptors. However, the escort fighters were not to initiate air duels before the target area was reached. If they were drawn into air combat before the target area was reached, they were not to depart from their general paths to seek vantage points. The reason for such an order was because the tokko aircraft must be guarded until the moment of attack. Any deviation in the flight paths on the part of the escort aircraft might create such a great distance between the escort aircraft and the kamikaze aircraft that catch up became impossible, leaving the special attack aircraft undefended when they reach the target area.

During take off, pilots were instructed to not allow the cheering comrades to distract the take off procedures. After taking off, they kept the nose of their aircraft from rising too soon, maintaining an altitude of 50 meters while gaining air speed before climbing to cruising altitude. Finally, aircraft of a special attack force tend to take off successively with minimal time lapse between each launch; this prevented aircraft that took off earlier to have to circle the airfield waiting for the other aircraft. Aircraft typically took off in 100 meter intervals to prevent circling.

Tokko pilots were instructed to choose fleet carriers and escort carriers as their primary targets. As for the points of aim, special attack pilots were instructed to hit specific areas of each ship type. Against carriers, the most desirable point of aim was the central elevator where even a less than perfect attack might render the carrier's function useless. Secondary points of aim against carriers were other elevators and the base of the bridge. Against other ship types, the base of the bridge or the area between the bridge and the center of the ship were both desirable. Like carriers, taking out the bridge of a ship meant disabling the ship's combat-worthiness at least temporarily. Against ships of equal or smaller size of destroyers, a single successful hit between the bridge and the center of the target ship might cause it to break in half and sink. The points of aim, therefore, were determined based upon the desire to cause the greatest amount of damage with the least expenditure in aircraft and lives. Although pilots were made aware of the points of aim for smaller ships, many air group commanders discourage attacks on targets unworthy of a tokko attack; instead, some of the pilots were instructed to return to base if they could not locate an enemy carrier, battleship, or cruiser.

Escorting fighters sometimes returned to base reporting that some special attack aircraft crashed into the target vessel without causing an explosion. It was determined that some pilots, in the heat of the moment, would forget to release the bomb safety before hitting their targets. Standard operation procedure disallowed pilots from disengaging the bomb fuse safety before battle, because if the bombs were not expended before landing, they must be wastefully jettisoned into the ocean for a safe landing. Therefore, it became the responsibility of the escort pilots to fly close to the tokko aircraft before the dives to make a visual inspection. If they believe the bomb fuse safety were still engaged, they would remind the tokko pilots via hand signals or radio.

During the diving attack, the tokko aircraft might approach the enemy vessel two different ways. The first method was the high attitude approach, where the aircraft approached the target at about 6,000 to 7,000 meters. The high altitude was vulnerable enemy radar or visual detection, but it took time for enemy fighters to reach the high altitude to intercept. If the enemy interceptor did reach the attack formation, it was hoped that the enemy pilots' ability to fight effectively might be reduced due to the thinner oxygen content of high altitude air. As the special attack aircraft approached, it began a shallow 20 degree dive until it reached about 1,000 to 2,000 meters in altitude, and then it dove sharply at 45 to 55 degrees, crashing toward the enemy vessel. Pilots were told to ensure the final dive angle would not be so steep that the aircraft might become out of control and miss the target.

An extremely low altitude approach was also believed to be effective. With this method, the tokko aircraft hugged the ocean at a height of mere 10 to 15 meters while approaching the target area, avoiding radar and visual detection. However, as the aircraft neared the target, it must quickly climb to 400 to 500 meters in altitude, then begin a dive for the target vessel.

British Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm pilot Lieutenant Commander Mike Crosley of 880 Naval Air Squadron aboard HMS Implacable commented after witnessing several tokko special attacks:

Ultimately, aerial special attack did not improve the Japanese ability to defend the home islands significantly; the 296 tokko aircraft that had successfully hit an Allied shipping only managed to sink 45 ships, and most of them were targets of relatively less value such as destroyers and landing ships. The Japanese leadership continued to be blinded by optimism, however. A conference at the 6th Air Army headquarters in Jul 1945, for example, concluded that aerial special attacks could destroy as much as a third of the Allied invasion force sailing for Japan when the invasion came. The Japanese Navy was slightly more conservative in its faith in special attacks, but it was still plagued by over-confidence; the admirals believed that they would be able to organize a fleet of 2,400 tokko aircraft, and about 400 of them would be able to hit American ships of tactical value.

Sources:

Rikihei Inoguchi and Tadashi Nakajima, The Divine Wind

Donald Nijboer, Seafire vs A6M Zero

Steven Zaloga, Kamikaze

Last Major Update: Nov 2006

Tokko "Kamikaze" Special Attack Doctrine Timeline

| 25 Oct 1944 | During the first major special attack conducted by the Japanese Navy, pilot Yukio Seki sank carrier USS St. Lo while another suicide pilot damaged carrier USS Santee. |

| 1 Nov 1944 | A battleship force on station at the northern entrance to Surigao Strait consisting of battleships USS Mississippi, California, and Pennsylvania screened by cruisers USS Phoenix, Boise, Nashville, and HMAS Shropshire along with destroyers Ammen, Bush, Leutze, Newcomb, Bennion, Heywood L. Edwards, Robinson, Richard P. Leary, Bryant, and Claxton came under an intense Japanese air attacking force that included special attack aircraft. USS Ammen sustained a glancing blow from a Yokosuka P1Y 'Francis' that caused considerable topside damage and killed 5 men. An Aichi D3A 'Val' crashed across Abner Read's main deck as it dropped a bomb down one the destroyer's stacks that exploded in the engine room. Abner Read jettisoned her torpedoes which immediately began their runs toward other ships in the group. Abner Read began sinking by the stern and 20 minutes after the attack, she rolled over and sank. 24 were killed. Meanwhile, Mississippi and Nashville had to take emergency evasive actions to avoid the torpedoes. |

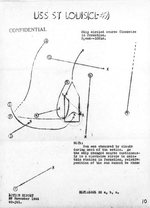

| 27 Nov 1944 | US Navy Task Group 77.2 consisting of battleships USS Maryland, USS West Virginia, USS Colorado, and USS New Mexico, cruisers USS Denver, USS St. Louis, USS Columbia, USS Minneapolis, and USS Montpelier, destroyers USS Nicholas, USS Waller, USS Eaton, USS Cony, USS Mustin, USS Conway, USS Pringle, USS Lang, USS Sigourney, USS Saufley, USS Aulick, USS Renshaw, USS Taylor, USS Edwards, and USS Mugford, tanker USS Caribou, and other patrol craft were patrolling in Leyte Gulf, Philippines when the group came under a concentrated Japanese special air attack from 20 to 30 aircraft. All but two of the Japanese planes dived on the formation in the sustained attack. Submarine chaser SC-744 was sunk and battleship Colorado and cruisers St. Louis and Montpelier were damaged. |

| 29 Nov 1944 | US Navy Task Group 77.2 consisting of battleships USS Maryland, USS West Virginia, and USS New Mexico, cruisers USS Denver, USS Columbia, USS Minneapolis, USS Montpelier, and USS Portland, destroyers USS Nicholas, USS Waller, USS Cony, USS Conway, USS Pringle, USS Lang, USS Saufley, USS Aulick, USS Renshaw, USS Edwards, USS Mugford, and USS Connor, and other patrol craft were patrolling in Leyte Gulf, Philippines when the group came under a Japanese air attack where special attack aircraft damaged Maryland, Saufley, and Aulick. |

| 5 Dec 1944 | While returning to San Pedro Bay, destroyer USS Shaw withstood an aerial special attack when a Japanese plane dove on the ship and crashed into the sea 25 yards off Shaw's port bow. Shaw sustained no damage. |

| 9 Dec 1944 | Destroyer USS Shaw departed Leyte Gulf bound for Hollandia (now Jayapura) with 78 survivors of the destroyer USS Ward that had been sunk by special attack aircraft two days earlier. |

| 13 Dec 1944 | In the late afternoon south of Mindoro, Philippine Islands, a special attack aircraft struck light cruiser USS Nashville amidships, killing 133 and wounding 190. Two hours later, another special attack aircraft struck, hitting destroyer USS Haraden. |

| 5 Jan 1945 | Destroyer USS Helm was struck by a Nakajima Ki-43 'Oscar' special attack fighter that damaged Helm's searchlight and injured six men. |

| 5 Apr 1945 | SS Hobbs Victory was struck by Japanese special attack aircraft while at anchor between Kuba and Aka Islands near Okinawa, Japan. She steamed into the East China Sea as the ships in the anchorage dispersed. She was discovered by the Japanese and was struck by another special attack aircraft, destroying her port side boiler and rendering her dead in the water. |

| 6 Apr 1945 | SS Hobbs Victory, struck by two special attack aircraft on the previous day, was destroyed in the East China Sea when the ammunition in her cargo hold exploded amidst firefighting efforts. |

| 27 Apr 1945 | Northwest of Okinawa, destroyer USS Ralph Talbot was struck by a special attack aircraft and nearly struck by another. The result was five men killed, many more wounded, and moderate damage to the ship. |

| 28 Apr 1945 | Japanese special attack aircraft damaged 5 destroyers, 2 hospital ships, and victory ship Bozeman Victory off Okinawa, Japan. None of the four G4M bombers carrying Ohka special attack aircraft hit their targets. |

Photographs

|  |

Videos

|

Maps

|

Tokko "Kamikaze" Special Attack Doctrine Interactive Map

Please consider supporting us on Patreon. Even $1 per month will go a long way! Thank you. Please help us spread the word: Stay updated with WW2DB: |

Visitor Submitted Comments

10 May 2017 11:01:42 AM

Japan was a tiny island nation. It's principle fighting force, its navy, was destroyed 6 mos. into the War. Without its navy, it was not able to effectively equip and/or supply its forces in the outlying areas. Those forces must have had dwindling oil supplies, food, ammunition, medicine, & other critically needed items.

Japan was effectively blockaded at the end of the war. Nothing could get in & nothing could get out.

Meanwhile, General Lemay firebombed its cities using highly flammable napalm to ensure maximum damage. Nearly all of Japan's manufacturing capacity was destroyed & much of Japan's population was rendered homeless. Sixty-one major Japanese cities were reduced to rubble.

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm

www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/COMM.10.5.03.HTM

www.commondreams.org/headlines02/0314-01.htm

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm

Without fuel & munitions, the Japanese turned its planes into weapons of last resort. It was like having their soldiers throw their rifles at the enemy when they ran out of bullets.

Hollywood created the myth that the Japanese would never surrender. But 600,000 of Japan's finest fighting forces surrendered to the Soviets after a mere two weeks of fighting in Manchuria in 1945.

The facts don't support the continuing myths.

All visitor submitted comments are opinions of those making the submissions and do not reflect views of WW2DB.

- » US State Lawmaker John Winter Caught Using Racial Slur "Jap" and Apologized (11 Jun 2025)

- » Köln/Cologne Evacuated After Discovery of WW2 Bombs (4 Jun 2025)

- » US Women's Army Corps "Six Triple Eight" Awarded with Congressional Gold Medal (30 Apr 2025)

- » Race, Holocaust, and African-American WW2 Histories Removed from the US Naval Academy Library (7 Apr 2025)

- » US Government Plans to Purge WW2 Information (17 Mar 2025)

- » See all news

|  |

- » 1,177 biographies

- » 337 events

- » 44,933 timeline entries

- » 1,245 ships

- » 350 aircraft models

- » 207 vehicle models

- » 376 weapon models

- » 123 historical documents

- » 261 facilities

- » 470 book reviews

- » 28,474 photos

- » 365 maps

Thomas Dodd, late 1945

15 May 2011 06:39:20 PM

Interesting article.